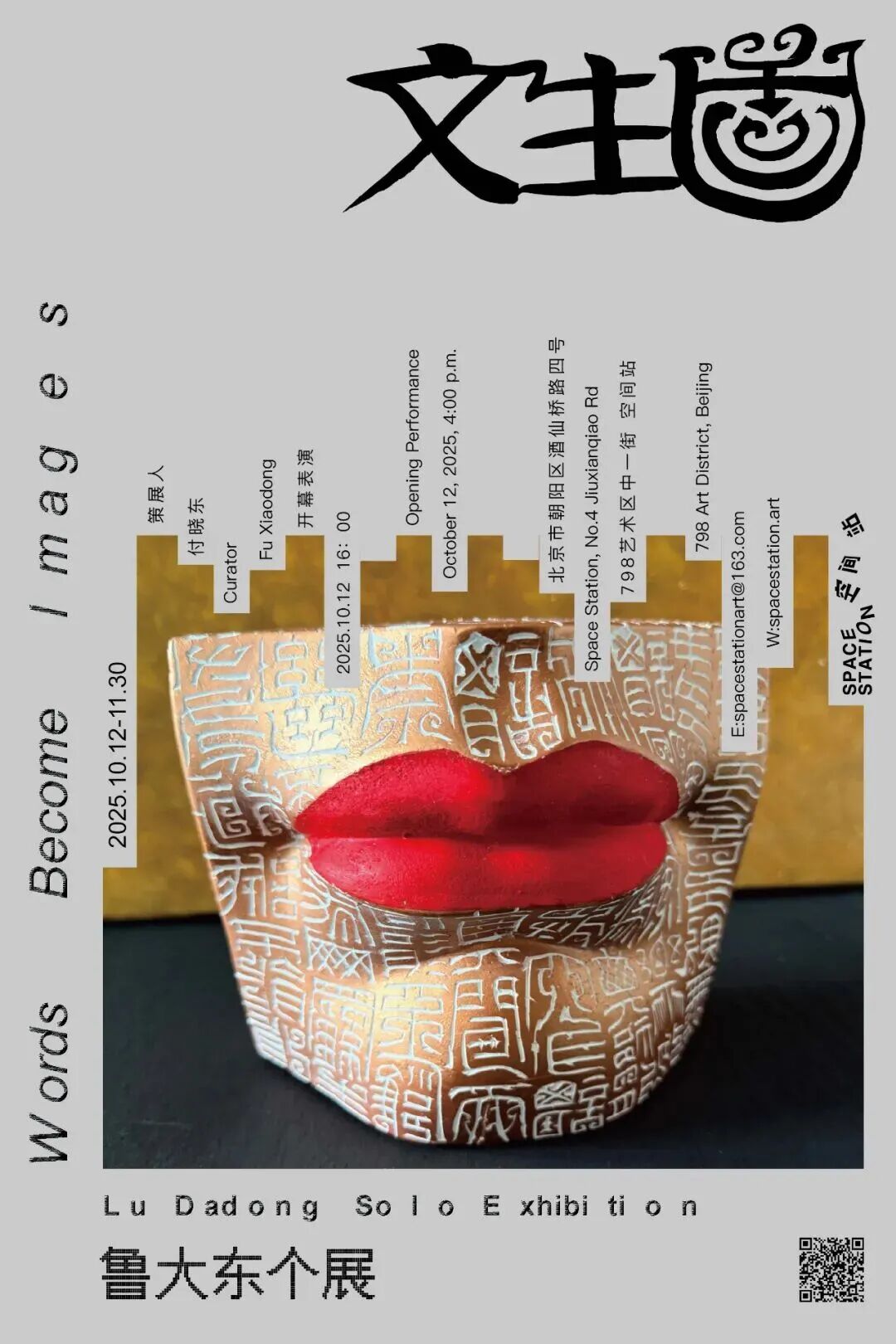

鲁大东:文生图

Lu Dadong:Words Become Images

展期:2025年10月12日—11月30日

开幕:2025年10月12日 16:00

艺术家:鲁大东

地点:空间站|北京市朝阳区酒仙桥路四号798艺术区中一街

延伸阅读:

【空间站】鲁大东个展「真诰」学术主持:袁宁杰《钦安殿藏道教令牌初探》

文生图,横著写,左读也可以,图生文。顾名思义,望文生义,因文生图,以图生文,因文字而生发图像,因图像而激发文字。与现在AI无关,与未来AI有关。It is text generating images, which can also be read from the left when written horizontally. As the name suggests, images are generated from text, and text is inspired by images. It has nothing to do with current AI, but related to future AI.

文:鲁大东

文生图,横著写,左读也可以,图生文。顾名思义,望文生义,因文生图,以图生文,因文字而生发图像,因图像而激发文字。与现在AI无关,与未来AI有关。

是文生图,非文生图,即说文生图。

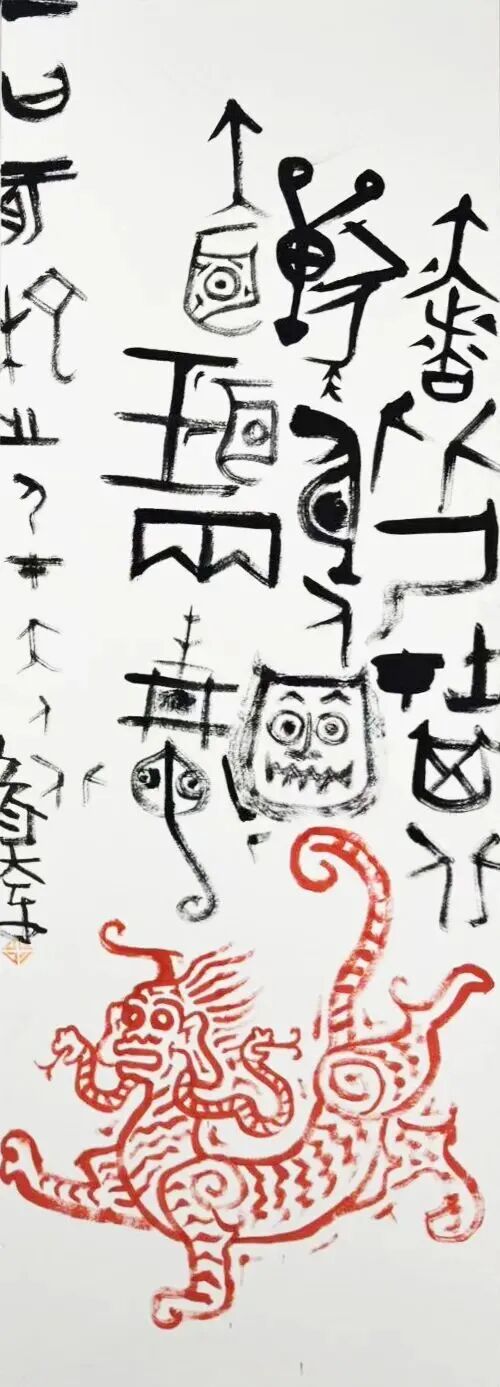

杨晓能的专著Reflections of Early China,把之前被叫做饕餮纹之类的青铜纹饰叫做Decor、之前被叫做族徽的文字叫做Pictographs和Pictorial Inscriptions,铭文与图像一并讨论,不分開。所以中译本叫《另一种古史》。

秦兼併六国,书同文,有八体,其中大篆、小篆、隶书是正体字,还有刻符、虫书、摹印、署书、殳书五种应用字体,现在的标准,都可以叫美术字。

王莽时有六书,篆书和左书(隶书)是正经字,缪篆和鸟虫书是应用体。更早的古文和奇字,后来外号叫蝌蚪文。

铜器、兵器、印章、铜镜、幡信,种种器物,文字离開图像之后再次图像化。

然后就是上层士人竞相展示恶趣味的几个世纪,从蔡邕、韦诞,到二王领衔的王谢家族,少年崇仿,家藏纸贵。写绘在装饰繁丽屏风上的花体,从王愔《文字志》上的三十六种,到南齐萧子良《古今篆隶文体》五十二种,南齐末王融《图古今杂体》六十四种,到梁庾元威《论书》已经凑到一百种。

屏风上如此,匾额上如此,志墓石上如此,寺庙山崖上也如此。

不仅是书写,还要彩绘,还要贴金错银,还要放大浮雕。

文字产生两千年才有纸,纸是降维材质。

唐孙过庭《书谱》,说这些杂体“巧涉丹青,工亏翰墨”,不是泼凉水,只是说赛道不同。

从氏族到文人,口味也在转变。

精巧华贵的东西不易存久,即使是金石也不会不朽。现代人书法史的叙事,面对缺乏图像只剩骈俪文辞的中古士族文化游戏,口气中满是鄙夷。

这些年我读书不多,看图不少,喜欢望图生文,看现在的文生图,书法部分投餵不行,也暗自著急,于是借助空间站,试图搅浑图文之水。

图文互生,将俟来日。

石膏篆刻、综合材料

Plaster Seal Carving, Mixed Media

17x8x14.5cm

2025作品以“金人三缄其口”典故为引,用石膏翻制秦汉封泥形制,却将印面文字压成无法发音的鸟虫篆符号。材质轻脆与金属浇铸的“缺席”并置,暗示制度规训下的失语;印钮残缺、边缘剥落,仿佛历史碎片在当代脱锚。鲁大东借此质问:当文字被抽离读音与意义,仅作为图像遗存时,是否仍拥有“铭刻”权力?

After Qin unified the Six States and decreed the standardization of script, eight types of writing were said to exist. Among them, Great Seal Script (大篆), Small Seal Script (小篆), and Clerical Script (隸書) were considered formal hands. The remaining five—Tally Script (刻符), Bird-and-Insect Script (蟲書), Seal-Imitation Script (摹印), Official Script (署書), and Halberd Script (殳書)—were functional or decorative, what we might now call artistic lettering.

During Wang Mang’s reign, the sixfold classification of script distinguished Seal Script and Left Script (another form of Clerical Script) as normative, while Variant Seal and Bird-and-Insect Scripts served decorative purposes. Still earlier forms—Ancient Script and Strange Characters—were later nicknamed Tadpole Script for their curvilinear shapes.

石膏篆刻、综合材料

Plaster Seal Carving, Mixed Media

11x22x11cm

2025

On bronzes, weapons, seals, mirrors, and ritual banners, writing—once liberated from imagery—became pictorial once again.

What followed were centuries of cultivated excess among the elite. From Cai Yong and Wei Dan to the aristocratic Wang and Xie families, literati competed in displays of refined eccentricity. Young scholars emulated the fashion, and fine paper grew scarce. Their ornate calligraphy, painted on luxurious screens, was meticulously classified: from Wang Yin’s Treatise on Script (《文字志》) listing thirty-six styles, to Xiao Ziliang’s Ancient and Modern Seal and Clerical Styles (《古今篆隸文體》) listing fifty-two, to Wang Rong’s Illustrated Miscellaneous Scripts Ancient and Modern (《圖古今雜體》) with sixty-four. By the time of Yu Yuanwei’s On Calligraphy (《論書》) in the Liang dynasty, the number had reached one hundred.

油画布丙烯 Acrylic on Canvas

56x38cm

2025

Such proliferation appeared everywhere—on folding screens, plaques, epitaph stones, temple walls, and cliff inscriptions.

These characters were not only written but also painted, gilded, inlaid with silver, and carved in relief.

Jiuquanzi — Verdant Trees in Deep Spring

纸本水墨 Ink on paper

52x32cm

Paper, that “dimensional reduction” of material support, would not appear until nearly two millennia after the invention of writing. In Treatise on Calligraphy (《書譜》), Tang theorist Sun Guoting observed of such ornate scripts: “Their craft approaches painting, yet their brushwork falls short of true calligraphy.” His remark was not a dismissal but a distinction—acknowledging a divergence in artistic path.

From the ritual traditions of clans to the cultivated tastes of the literati, sensibilities shifted. The exquisite and the ornate seldom endure; even bronze and stone decay.

Dongxian Song — Jiangnan at Winter’s End

纸本水墨 Ink on paper

52x32cm

Modern histories of calligraphy, confronted with the fragmentary remnants of medieval aristocratic culture—texts without images, rhetoric without form—often speak with tones of condescension.

In recent years, I have read little but looked much.

Memorial of the Human Epoch

油画布丙烯 Acrylic on Canvas

66x55cm

2025

I take pleasure in reading images, in letting vision generate language. Confronting today’s versions of “when words become images,” I find the calligraphic sensibility lacking, and this fills me with quiet unease.

Thus, through the platform of the Space Station, I seek to stir the once-clear boundary between word and image.

Let them intertwine once more—

for words and images are mutually generative,

and the future will bear witness to their return.

By:Lu Dadong

Shan Hai Jing · Beyond the Eastern Seas

鲁大东

名齐,号启明、夷窠

蓬莱籍,1973年生于山东烟台

1995 浙江美术学院国画系书法篆刻专业,学士

2004 中国美术学院书法系,硕士

2017 中国美术学院书法系,博士

中国美术学院书法学院书法传播与教育系主任

中国美术学院现代书法研究中心副主任

与人乐队主唱